Racial Barriers to Public Housing

by Emily Meehan and Jack Dougherty

As we saw in the previous section, housing discrimination did not occur solely due to private individuals, but often as a result of deliberate actions by public policymakers. Yet in some cases, different levels of government came into direct conflict over this issue. During World War II, the Roosevelt administration clashed with West Hartford political leaders over the right of Black workers to reside in federal wartime housing. To manufacture weapons to defeat Germany and Japan, the United States Housing Authority (USHA) created shelter for thousands of wartime workers who migrated to work in factories in the city and suburbs of metropolitan Hartford. In comparison to the Federal Housing Administration, the USHA took a racially progressive stance in favor of housing blacks workers wherever need and space existed, even if that meant government-funded housing in virtually all-white neighborhoods. But in West Hartford, racism trumped patriotism. Suburban political leaders mobilized against federal authority to prevent Black workers from moving into their community. Even when Washington DC pushed back, local leaders prevailed by finding a legal loophole to block non-whites from moving in.

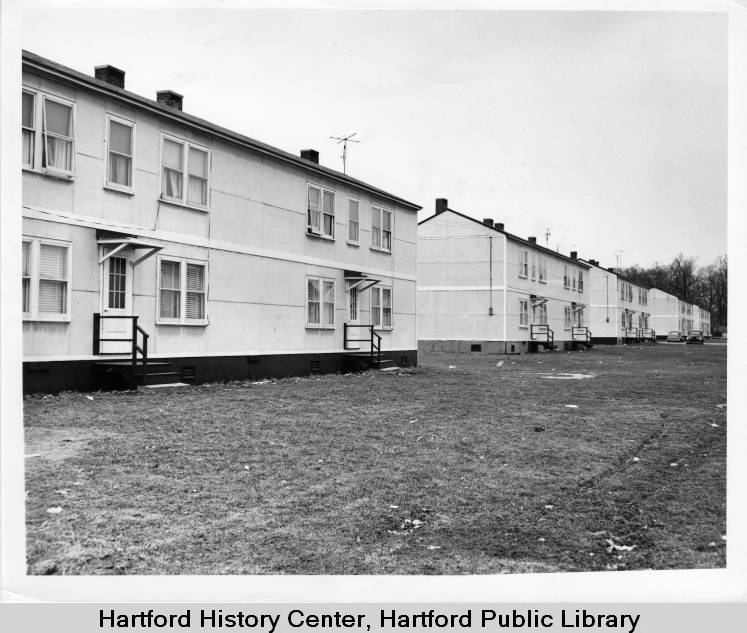

In 1943, a dispute arose in West Hartford over the Oakwood Acres public housing development, shown in Figure 2.26.72 Federal housing officials and West Hartford leaders clashed on whether or not Black workers should be allowed to live in this World War II public housing development, located in a virtually all-white town. During this period, public housing tracts were created to shelter the many war workers and their families drawn to the Hartford area by the availability of defense-related jobs. The United States government funded these developments; therefore, local housing officials needed to abide by federal laws regarding occupancy. Federal Housing authorities eventually did require West Hartford to admit Black workers; however, the White residents and town leaders prevailed by specifying residency criteria in such a way as to maintain the racial homogeneity of their community. Racist actions such as these, even when they occurred decades ago, have been factors in shaping the present-day demographics of West Hartford and other towns in the state.

Figure 2.26: Photo of Oakwood Acres public housing in West Hartford, from the Hartford Times, February 17, 1954, digitized by the Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library.

The advent of World War II brought significant changes to a country that had been in the grip of a deep financial depression. Across the nation, as people moved into cities looking for jobs in wartime defense industries, demand for housing soared. Often, that demand far exceeded the availability of properties to purchase or even rent. In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the United States Congress established the United States Housing Authority (USHA) and authorized it to build public housing units with the goal of providing adequate living quarters for war workers.73

An influx of White and Black wartime workers their families came to the greater Hartford area in the 1940s. They worked in defense factories, such as the Pratt & Whitney Machine Tool plant and the newer Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company. As a result, housing options were limited in the Hartford area. By August of 1943, 8,000 new housing units had been developed in Hartford and New Britain to accommodate the growing population. These apartment-style homes were built under the Hartford Housing Association (HHA) and paid for with federal funding from the USHA.74

According to a 1943 Hartford Courant report, “Connecticut has about half of all the government war housing constructed in New England. Half of the government housing in this state has been put up in the Hartford-New Britain area…” With these statistics, one might think that workers’ need for housing in Greater Hartford had been met. However, families and single Black war workers found it more difficult to procure homes. The Courant noted that “400 housing units for white in-migrant families” were being constructed and, in “the case of Negroes,” it was thought that “temporary dormitories” might be built if additional government grants could be obtained. Berkley Cox, chairman of the HHA called this situation “satisfactory.”75

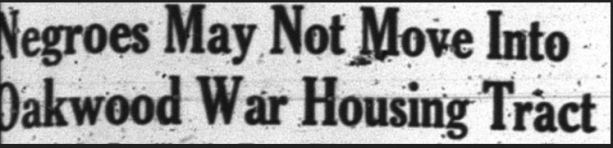

Figure 2.27: Headline from 1943 Metropolitan News stated that “Negroes may not move into Oakwood” wartime public housing in West Hartford. Digitized by West Hartford Public Library.

One unit developed under the HHA was the Oakwood Acres Housing Tract. Located on Oakwood Avenue in West Hartford, it spanned the area between St. Charles Street and Seymour Avenue. Contemporary descriptions present the Oakwood Acres’ living spaces as new, simplistic, and affordable. In 1943, only 14 out of the 300 apartments in the building were occupied at a time when many Black workers either had no place to live or could only find substandard accommodations. The federal government planned to use the complex to provide housing for these workers and their families.76

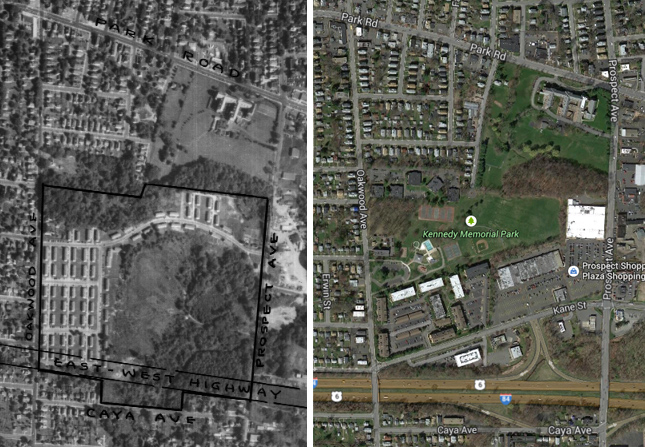

Figure 2.28: Aerial images of Oakwood Acres Housing Tract, in 1951 and today, on the West Hartford border with Hartford, from MAGIC UConn Libraries.

Because the government funded Oakwood Acres, the unit needed to abide by federal law, which stated that officials could not legally reject Black workers from applying for housing. West Hartford homeowners, living near Oakwood Acres, were quoted in a September 1943 issue of the Metropolitan News as being “alarmed” and “horrified” at the idea of “Negroes” living in their neighborhood. One woman said she and her family would move out the day after any Black residents moved in. The paper itself described the situation in harsh, racist language, calling it an “infiltration,” and reported the prevailing sentiment among community homeowners as being: “We don’t want them here.” The consensus among West Hartford realtors and homeowners, the newspaper reported, was that real estate values would show “an immediate and sharp” drop if “Negroes in any considerable number moved into town.”77

Furiously, homeowners wrote to the HHA and West Hartford Housing Authority (WHHA) asking if Black workers would indeed be admitted to Oakwood Acres. When the Hartford Courant posed the question to WHHA chairman Richard F. Jones, he equivocated, saying, “I won’t say we are and I won’t say we’re not going to admit Negroes… At the present time that is a topic we’d rather not publicize too much.” This prompted West Hartford residents to send petitions to their senators, Francis Maloney and John A Danaher, and congressman, William Miller. Miller responded that he would look into the issue.78

The United States Housing Authority responded with an ultimatum. They stated that it was unlawful to exclude occupants from Oakwood Acres based on race. Local housing officials were advised that unless the race restrictions were lifted, the federal government would step in. Under this decision, Black workers would be admitted if they applied for a unit. This angered many West Hartford homeowners, prompting the town’s housing officials to find a loophole. They decided to accept applications only from “Negroes with essential West Hartford industry jobs.” Officials made this ruling knowing that, at the time, only six Black families fit this criterion–and they had not expressed interest in living in Oakwood Acres. Ultimately, with this restrictive technicality in place, no Black war workers moved into the housing tract. The white West Hartford housing officials and their supporters had trumped the federal government. They found a way to circumvent federal guidelines and discourage Black workers from living in publicly funded housing within the town’s borders.79

In 1956, Oakwood Acres was demolished. It had become dilapidated and the people of West Hartford feared it made their neighborhood look like a “slum.”80 By destroying the unit, West Hartford also erased the physical remnants of this racist chapter in the town’s housing history. Today, West Hartford remains a predominately white community. One can argue that its demographics have been shaped, in part, by discriminatory housing practices of which the standoff over Oakwood Acres is but one example.

About the authors and contributors: Emily Meehan (Trinity 2016) wrote the first draft of this essay in the Cities Suburbs and Schools seminar, and published it in ConnecticutHistory.org.81 Jack Dougherty expanded the essay for publication in this book.

Hartford Times, “Oakwood Acres Temporary Housing, West Hartford” (Photograph, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library, February 17, 1954), https://www.flickr.com/photos/cthistoryonline/5717411442/in/set-72157626521582021.↩︎

Kristin M Szylvian, “The Federal Housing Program During World War II,” in From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth-Century America, ed. John F Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin M Szylvian (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), 121–38, https://books.google.com/books?id=YZ9mO3NLP90C&pg=PA121#v=onepage&q&f=false.↩︎

“1877 Worker Visits New Tool Plant,” Hartford Courant, October 29, 1941, http://www.proquest.com/hnphartfordcourant/docview/559524037/abstract/AC77F88C6CE3454EPQ/1; “Housing Reaches 8000 Mark in City and New Britain,” Hartford Courant, August 14, 1943, https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/historical-newspapers/housing-reaches-8000-mark-city-new-britain/docview/559829506/se-2?accountid=14405.↩︎

“Negroes May Occupy Oakwood Acres to Solve Rental Lag,” The Metropolitan News, September 30, 1943.↩︎

“Housing Official Noncommittal on Racial Question,” Hartford Courant, October 21, 1943, https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/hnphartfordcourant/docview/559844453/4279A3CDE13D4FE9PQ/1?accountid=14405; “Residents Ask Congressmen’s Aid on Negro Housing Threat,” Metropolitan News, November 4, 1943, https://history.westhartfordlibrary.org/items/show/420.↩︎

“Negroes May Not Move Into Oakwood War Housing Tract,” Metropolitan News, December 16, 1943, https://history.westhartfordlibrary.org/items/show/421; Katherine Ellen Winterbottom, “Beneath the Veneer,” The Spectator [West Hartford Historical Society Newsletter] Autumn (1998): 1, 10–14.↩︎

Tracey M. Wilson, “Resistance to Public Housing and Integration During World War II,” in Life in West Hartford (West Hartford, CT: West Hartford Historical Society and Noah Webster House, 2018), http://lifeinwesthartford.org/world-war-ii-era.html#resistance-to-public-housing-and-integration-during-world-war-ii.↩︎

Emily Meehan, “The Debate Over Who Could Occupy World War II Public Housing in West Hartford” (ConnecticutHistory.org, January 2014), http://connecticuthistory.org/the-debate-over-who-could-occupy-world-war-ii-public-housing-in-west-hartford/.↩︎

On The Line is copyrighted by Jack Dougherty and contributors and freely distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.