Restricting with Racial Covenants

by Tracey Wilson, Vianna Iorio, David K. Ware, June Gold, and Jack Dougherty

No persons of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race employed by an owner or tenant.

– High Ledge Homes on South Main Street, West Hartford, Connecticut, 1940.46

To some readers, this shockingly racist language might seem like a long-ago segregation policy from the Deep South. Instead, these words appear in official government land records in what some call the Deep North, and represents a hidden chapter in White suburban history, which needs to be revealed and reckoned with today.

When buyers and sellers of real estate agree on a contract, they usually sign a property deed or legal agreement to document the sale, and may decide to include a covenant to limit how the land may be used. For example, a seller might insert a covenant that forbids opening a business on property intended only for residential homes, in addition to any local laws or zoning ordinances governing land use. Beginning in the 1920s across the U.S., real estate developers, homeowners’ associations, and private owners commonly added race restrictive covenants like the one cited above to prohibit people outside of “the white race” from owning, using, or residing on property, with some exceptions for domestic servants. When property sellers file a deed with their local government, the town or county clerk records the transfer into the official land records, where any covenants become legally binding on future owners. For example, if property includes a racial covenant, a White resident with legal standing could bring a lawsuit to court to enforce the legal agreement and block a sale to a Black homebuyer. In this way, covenants became larger than the actions of racist individuals by growing into another form of government-supported housing segregation. After activists opposed racial covenants, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled them to be unenforceable in 1948, and the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 made them unlawful. Yet some local governments continued to accept and file racial covenants until courts stopped this practice in 1972. Even today, decades after the law changed, perhaps a million racial covenants still exist on the books in local government land record offices across the nation, while a newer generation of activists have made it easier for current homeowners to find and reject them.47

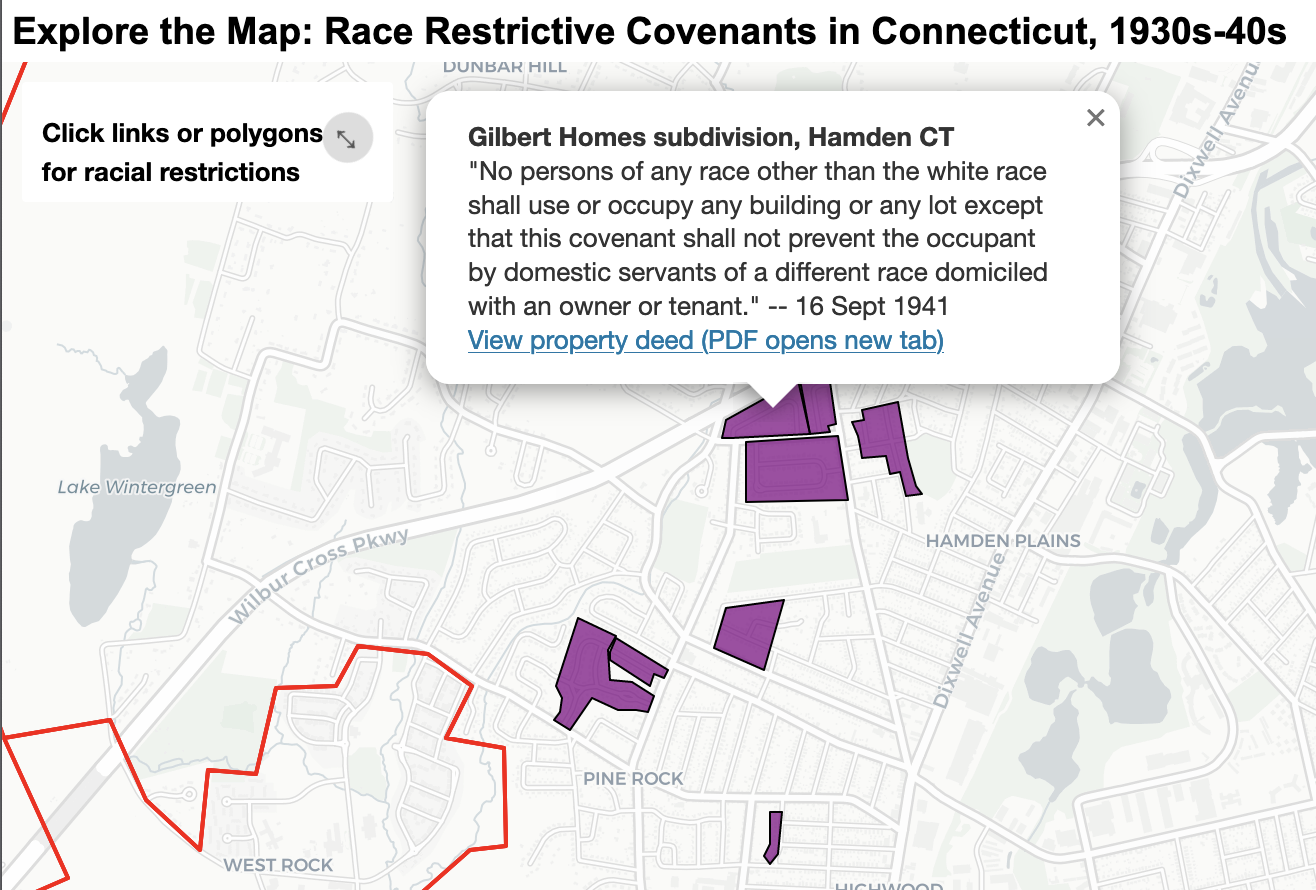

This chapter reveals the history of state-sponsored racial restrictions in Connecticut land records. So far we have searched land records in only a small number of the state’s 169 towns, but located over a thousand racial covenants that real estate developers placed on suburban homes and lakefront cottages from the 1930s to the 1950s, as shown in Figure 2.14. More work remains to be done to find and reject these racist covenants.48

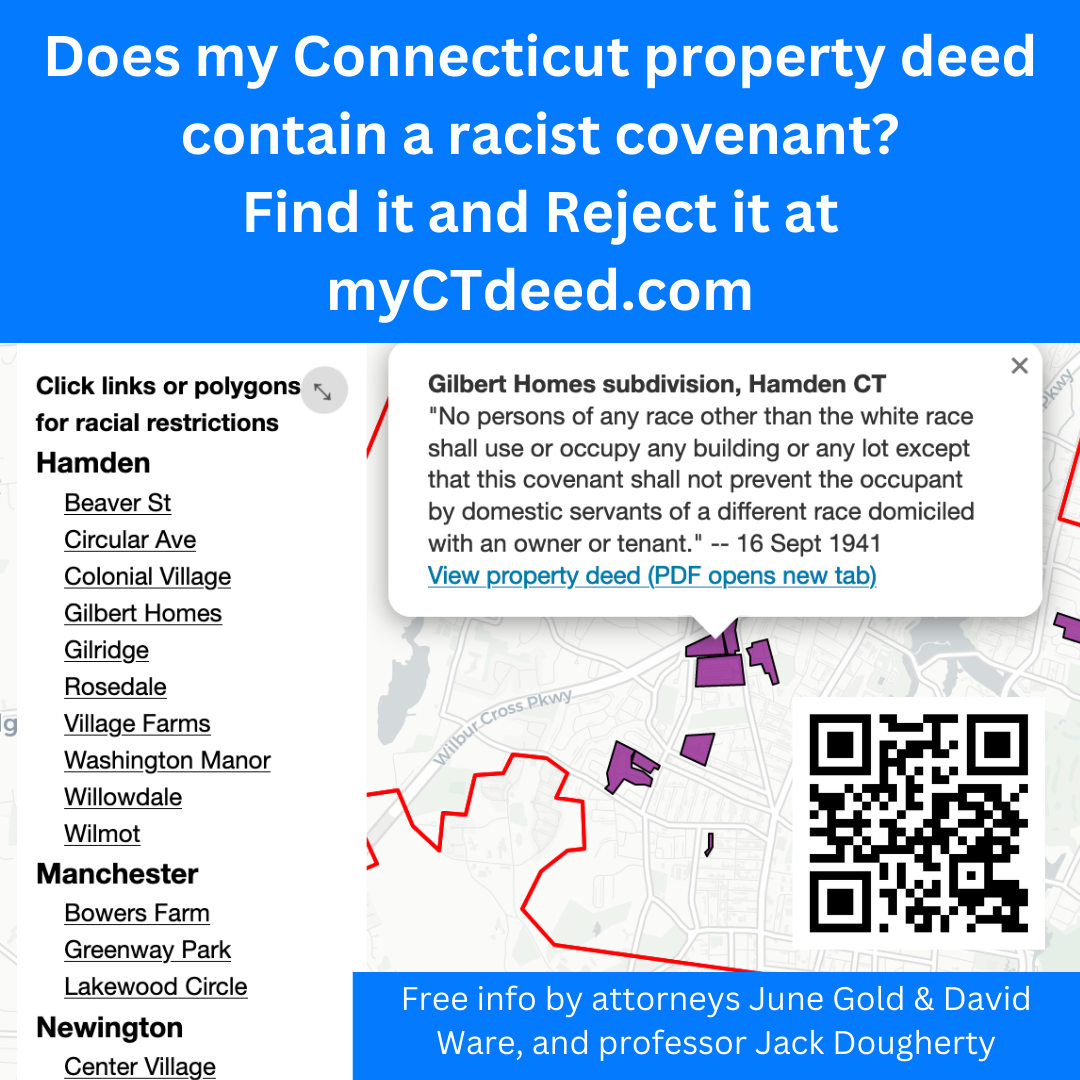

Learn how to find and reject racist covenants on our public outreach site: https://myCTdeed.com. Learn about How We Found Restrictive Covenants in this book. If you know of similar covenants with racial or religious restrictions anywhere in Connecticut, contact the authors.

Figure 2.14: Click links or polygons in the full-screen interactive map to view Connecticut neighborhoods where most or all properties include racist covenants by housing developers to prohibit occupants “other than the white race.” Although the US Supreme Court declared racial covenants unenforceable in 1948, and the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 made them unlawful, only in 2021 did Connecticut pass a law to make it easier for current owners to reject this language in official town land records. If you know of similar covenants with racial or religious restrictions anywhere in Connecticut, contact the authors. Research by June Gold, David Ware, Katie Campbell Levasseur, and Jack Dougherty. View historical sources and the code for this map, developed by Ilya Ilyankou and Jack Dougherty, based on an earlier version created with UConn MAGIC.

First, this chapter explains how race restrictive covenants arose in the nation beginning in the 1920s, and appeared in Connecticut property deeds and land agreements from the 1930s to the 1950s. Although racist covenants were more common in Northern and Western cities such as Seattle, Minneapolis, and Chicago, those we have found so far in Connecticut vary in concentration, with nearly 1 out of 4 homes affected in some suburban towns. Second, the chapter describes how Connecticut civil rights advocates challenged restrictive covenants as an “un-American” policy during the late 1940s, and helped shift public opinion as the US Supreme Court ruled them to be unenforceable in 1948. Third, the chapter explains how Connecticut legislators approved a 2021 law that enables current homeowners to easily reject racist covenants in the legal record, without erasing them from our collective memory. Overall, their historical legacy remains with us in two ways. On a tangible level, White homebuyers who purchased covenant-protected property gained financial benefits—meaning higher home values in legally-guaranteed all-White neighborhoods—that they passed forward as inheritances to future family members. On a systemic level, uncovering the hidden history of racist covenants in the Deep North reminds us how Connecticut’s suburbs were shaped not simply by individual actions or market forces, but more broadly by government-supported White supremacy.

The Rise of Racial Covenants

The nation’s story of restrictive covenants begins with the U.S Supreme Court case Corrigan v. Buckley in 1921. White property owners in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington D.C. formed a property owners’ association that used racially restrictive covenants to keep out Black homebuyers. The dispute arose when White owner John Corrigan attempted to sell his house to an Black buyer, Irene Curtis, a violation of the property’s racial covenant. Learning of this violation, White neighbor Irene Buckley brought suit to enforce the race restrictive covenant and stop the property sale.

As the case worked its way through the nation’s legal system, courts upheld this new tool for racial barriers in housing. First, the District of Columbia Supreme Court approved the racial covenant and cited existing legal segregation in schools and public recreational facilities as precedent. Second, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals also approved the racial covenant and stated that Black owners were free to include the same kind of racially exclusive language against White buyers in their own property deeds. Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the lower court decisions in 1926 by refusing to hear the case on grounds that they lacked jurisdiction. When Justice Edward Sanford delivered the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion, he narrowly defined the Constitution’s guarantee that no person should “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” as it applied to Corrigan v. Buckley. While the Fifth Amendment limited the actions of the federal government, Sanford asserted that it did not apply to individuals entering into a private contact, such as a restrictive covenant. Moreover, he argued that the Thirteenth Amendment did not protect individual rights of Black citizens, and the Fourteenth Amendment again referred to actions of the state, not of private individuals. Therefore, the 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley decision reaffirmed the right of property owners to legally enforce race restrictive covenants, while ignoring that the court system itself acted as governmental support for segregation. Their interpretation of the Constitution would prevail for the next two decades.49

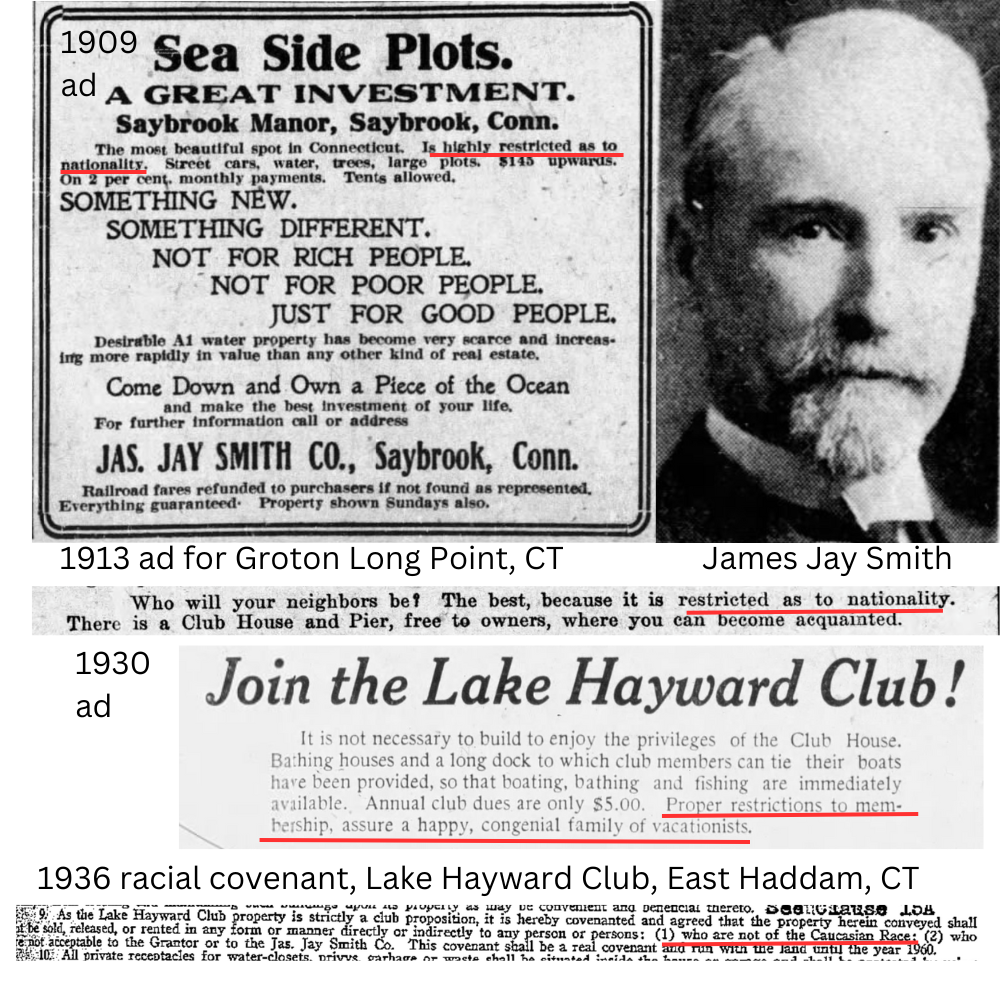

In Connecticut, James Jay Smith was one of the earliest real estate developers to act on the Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of racial covenants. Two decades earlier, when his Jas. Jay Smith Company began selling Connecticut shoreline property, he openly publicized that sales were restricted by nationality, presumably to prohibit Jews and other recent immigrants. Smith advertised Old Saybrook oceanfront property in 1909 as “not for rich people, not for poor people, just for good people,” but prominently added it was “highly restricted as to nationality,” as shown in Figure 2.15. Smith ran the same ad not only in local newspapers, but also in broader publications such as the Literary Digest, and used the same wording for Westchester NY property in the New York Times that same year. By 1913, Smith had transformed prejudice into a rhyming sales jingle. “Who will your neighbors be? The best, because it is restricted as to nationality” sang his ad for beach property at Groton Long Point, CT. But in these early years, Smith’s restrictions apparently were not yet encoded into local government land records. Instead, Smith’s developments relied on rules as a private club. Speaking to the Niantic (CT) Chamber of Commerce in 1932, his son Avy B. Smith explained that the Black Point Club development, which numbered 124 homes at that time, was “called a club” because “in so doing before any one could purchase property they were investigated, which keeps out many objectionables.”50

After the Supreme Court’s 1926 approval of racial covenants, Smith took advantage of legalized racial restrictions when he began selling Connecticut lakefront property in the early 1930s. When Smith’s Shore & Lake Corporation launched the Lake Hayward Club development in East Haddam, they continued to advertise “restrictive” club membership, but also wrote racial covenants directly into property deeds, and filed them with the town government clerk, where they became enforceable by the courts. “As the Lake Hayward Club property is strictly a club proposition, it is hereby covenanted,” the deed stated, and could not be sold or rented to any persons “(1) who are not of the Caucasian Race; (2) who are not acceptable to the Grantor (seller) or to the Jas. Jay Smith Co.” The Lake Hayward Club summer cottages, tennis courts, and boating facilities “proved so attractive to causal visitors from New York and elsewhere,” Smith told the press in 1934, that he hired “a special constable to keep off trespassers…(and) to patrol the tract against undesirable visitors.” We estimate that Smith’s racist covenants reached over 400 homes at Lake Hayward, the largest single development we have found so far in our Connecticut research.51

Figure 2.15: Over time, real estate developer James Jay Smith supplemented his nationality-restricted private clubs with racist covenants written into property deeds and recorded by town government clerks. Images copyrighted 1909 and 1942 obituary photo (Hartford Courant); 1913 (The Day, New London CT); 1930 (The Journal, Meriden CT), reprinted here under fair-use guidelines; 1936 covenant from Town of East Haddam, public domain.

In Connecticut’s emerging suburbs, real estate developers began adding racial covenants to selected neighborhoods by the late 1930s. Previously during the 1910s and perhaps earlier, individual property owners had begun adding non-racial types of deed restrictions to increase the land values. For example in West Hartford, some owners placed home-value restrictions in their deeds, requiring that future homes constructed on the land must be built above a minimum size or sold above a minimum dollar amount. Some owners began to add “nuisance” restrictions to prohibit chicken coops or noxious fumes, again to raise property values. Finally, some West Hartford real estate developers began to add home-value restrictions across entire subdivisions, setting the stage for exclusionary zoning policies that the Town would later adopt in 1924, as described in this book chapter. While these home-value restrictions effectively limited neighborhoods to wealthier White families, they did not yet contain explicitly racist prohibitions.

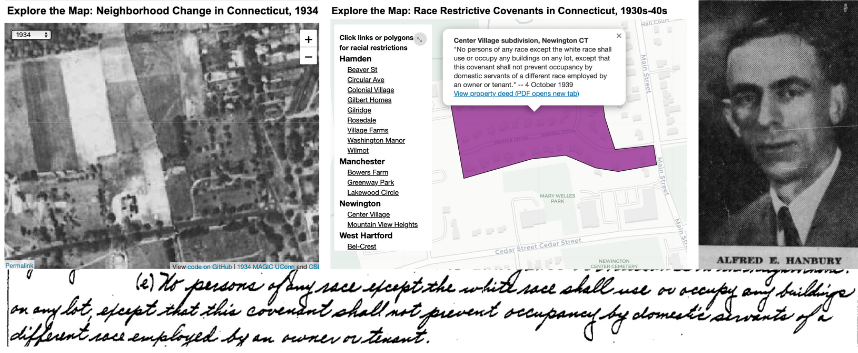

The earliest racial covenant we have found in Hartford-area suburbs appeared in late 1939 for an entire subdivision in Newington, a town on Hartford’s southern border, based on research by David Ware. During the Depression, real estate developers sought ways to convert rural farmland to prospective homes and make it more attractive to city dwellers to purchase. One developer was Alfred E. Hanbury, who renamed farmland he purchased near the town’s crossroads as the “Center Village” subdivision for future homes. Hanbury told city news reporters he was “optimistic concern[ing] the future of Newington as a residential community,” with its gas and electric utilities, easy trolley commute to Hartford, and affordable Federal Housing Administration mortgages, a topic described in this book chapter. Hanbury added several restrictions to a handwritten deed he filed when selling five property lots to homebuyers in October 1939. First, he required that only single-family homes could be constructed, on plots of land no smaller than about one-fifth of an acre, with no noxious or offensive businesses that might annoy neighbors. Later in the deed, he added an explicitly racist restriction, possibly drawn from language he had seen other developers using elsewhere. “No persons of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any buildings on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race employed by an owner or tenant,” as shown in Figure 2.16. Selling homes was challenging during the Depression and World War II, but Hanbury finally sold 47 units at Center Village after the war and was selected as one of the first directors of the Home Builders Association of Hartford County, reflecting his status within the profession. Interestingly, Hanbury did not include racial covenants to two of his post-war Newington housing developments: Alandale and Belden Acres.52

Figure 2.16: Alfred Hanbury developed Newington farmland as shown in 1934 aerial image into the Center Village housing subdivision and added a race restrictive covenant in 1939. Image of Hanbury copyrighted 1950 by Hartford Courant, reprinted here under fair-use guidelines. Aerial map digitized by UConn MAGIC, and document from Town of Newington property records, both in public domain.

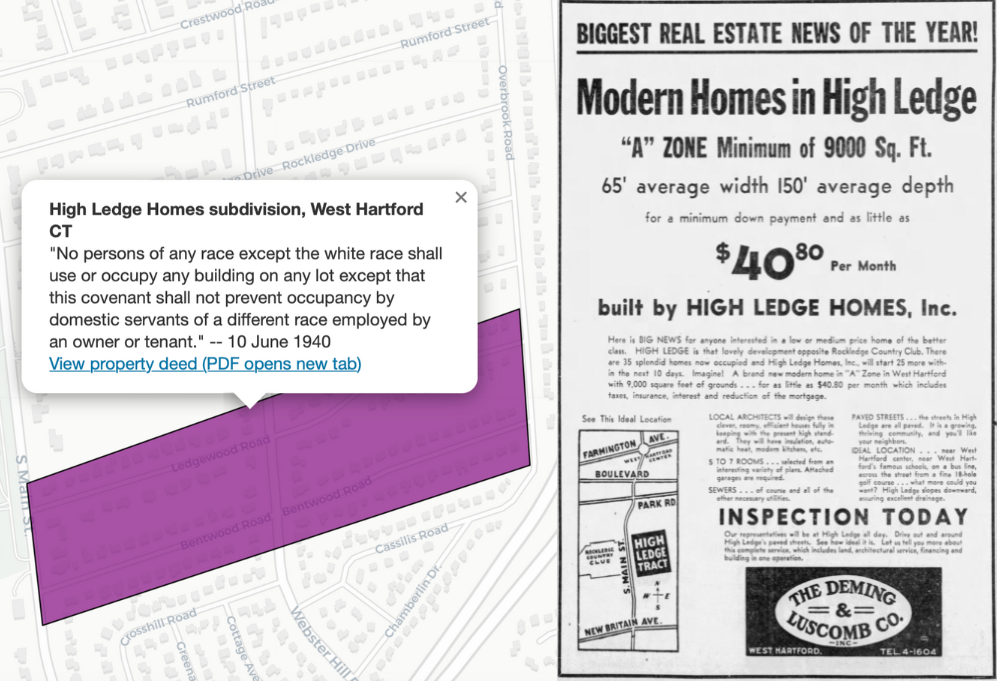

In nearby West Hartford, some real estate developers also added racial covenants to attract homebuyers to more exclusive all-White suburban neighborhoods. Edward Hammel, president of High Ledge Homes, Inc., added the first racial covenant we have found in West Hartford in 1940. Described as a “builder of fine homes” in wealthy areas of Westchester County, New York, and Fairfield County, Connecticut, Hammel introduced new methods to make unsold property more marketable. Hammel purchased a subdivision on South Main Street, across from the Rockledge Gold Course, consisting of 84 property lots that the prior owner, developer Robert Bent, had not been able to sell during the Depression. Hammel’s land records added a “uniform plan of development” for single-family homes that also prohibited occupants “of any race except the white race.” Although High Ledge Homes did not openly publicize their White-only covenant, their 1940 advertising promised homebuyers that with A-level exclusionary zoning requirements, “you’ll like your neighbors,” as shown in Figure 2.17. The pitch also mentioned “West Hartford’s famous schools,” one of the earliest real estate advertising references to this young suburb’s public education system, and perhaps a premature one for this period, when Hartford’s city schools still had a stronger reputation. By 1941, at least four more West Hartford developers followed Hammel’s lead and added racial covenants to their subdivisions.53

Figure 2.17: Although High Ledge Homes did not openly publicize their White-only covenant (map on left), their 1940 advertising promised homebuyers that with A-level exclusionary zoning requirements, “you’ll like your neighbors.” Image copyrighted 1940 by Hartford Courant, reprinted under fair-use guidelines.

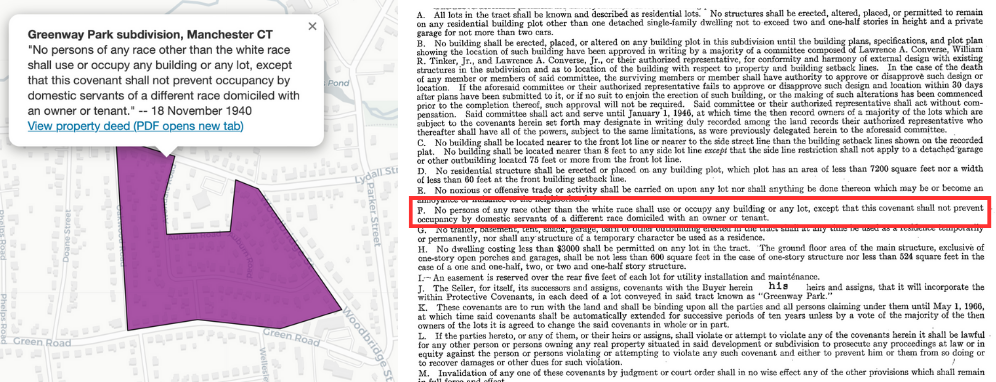

In Manchester, a suburb located to the east of Hartford, at least three real estate developers included race restrictive covenants in their subdivisions in the early 1940s, according to attorney David Ware. At this stage, the ban against occupants “other than the white race” for housing developments such as Greenway Park, now appeared on pre-printed forms designed for mass duplication to individual buyers, as shown in Figure 2.18. But Ware points out how racial covenants still remained “hidden” in several ways. First, while land records are public documents in the town clerk’s office, individual pages inside large bound volumes were not easily searchable or copied in the 1940s, and still remain difficult to find in today’s digital age, as described in How We Found Restrictive Covenants in this book. Second, the White-only restriction was buried in section F in a long page (sections A-M) of seemingly innocuous restrictions, meaning it would not stand out to homeowners unless they carefully read every line of their property deed. Third, Ware argues that racial covenants were “temporally camouflaged” because the White-only language only appeared in the deeds originally prepared by the developer and delivered to the initial buy of subdivision lots. For all future sales, the deed simply stated that the property was “subject to certain restrictions of record,” which disguised its racist origins. For example, when Ware’s parents bought their Manchester home in 1950, their property deed vaguely stated that “said premises are subject to certain restrictive covenants of record” – which went back five prior transfers – to the original racial restriction in the 1942 deed by Lawrence Converse, present of the Greenway Park, Inc. development. Racism was legally powerful yet well-hidden in the Deep North.54

Figure 2.18: In Manchester, The Greenway Company placed racial covenants in pre-printed forms in 1940, seen only by homebuyers who read the fine print on the original property deed. View full-size document from Town of Manchester property records, public domain.

Elsewhere in Connecticut, the racial covenants appeared in higher concentrations than Hartford-area suburbs. In Hamden, a suburb north of New Haven, real estate developers added White-only restrictions to at least 11 subdivisions during the 1940s, according to attorney June Gold. Many of these race-restricted subdivisions were located between the New Haven city boundary and the planned route of the Wilbur Cross Parkway, shown in Figure 2.19. Seven subdivisions were connected to three developers whose names appear multiple times in the land records: Joseph Maselli, Veggo F. Larsen, and Thomas A. Laydon. In total, Hamden developers placed racial covenants on an estimated 521 homes.55

Figure 2.19: Hamden developers added White-only restrictions to several suburban subdivisions located between the New Haven city border (red line) and the planned route of the Wilbur Cross Parkway in the early 1940s. Explore the interactive covenants map.

While we have searched property deeds in only a small number of Connecticut’s 169 towns, we have found over a thousand of White-only restrictions, as shown in Figure 2.20, dating from the early 1930s to the early 1950s. But the concentration of racist covenants varies widely across the state. In Manchester, only 3.5 percent (248 out of approximately 7,100) of residential building lots approved by town officials between 1910-1950 included racial covenants. In West Hartford, only 6 percent (190 out of approximately 3020) of buildings constructed during the 1940s had racial covenants. Yet in Hamden, 23 percent (521 out of 2297) of homes built during the 1940s included racial covenants. To be clear, these explicit White-only covenants reflected not only private transactions between buyers and sellers, but a broader pattern of government-sponsored segregated housing practices—such as federal lending policies, public housing barriers, and exclusionary zoning ordinances–that restricted non-White and lower-income residents from moving into outlying towns, as described in other chapters in this book. More research remains to be done to uncover more of Connecticut’s past.56

Figure 2.20: View the table and calculations, by Jack Dougherty, June Gold, and David Ware.

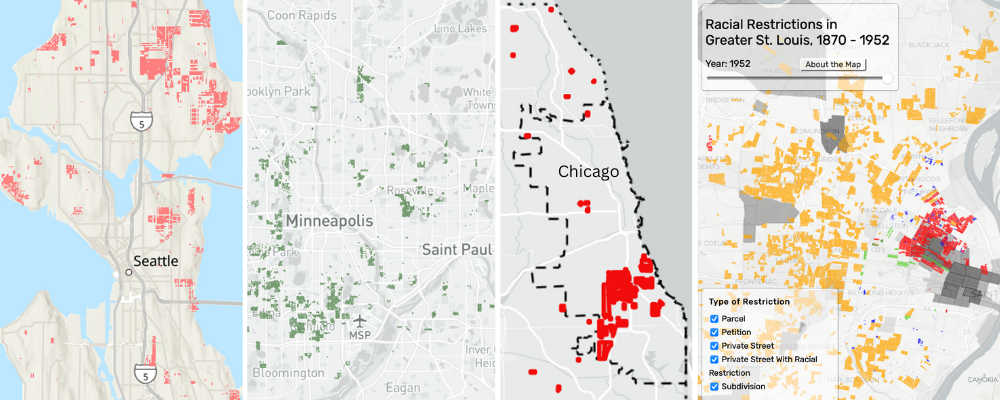

Compared to Connecticut, restrictive covenants were more common in other US cities, with some estimates of properties with racial restrictions ranging as high as 80 percent. Public history project teams have uncovered evidence and sparked action, according to the National Covenants Research Coalition, including those shown in Figure 2.21. One of the earliest to launch online was the Segregated Seattle project in 2005, where researchers have found White-only and anti-Jewish clauses in over 30,000 property deeds in King County to date, plus 20,000 more in other counties in Washington state. Their work pushed state legislators to approve a 2006 law to encourage homeowners to strike out racist covenants in the public record, and a 2023 law to provide compensation for victims. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul region, the Mapping Prejudice project began to document restrictive covenants in 2016 and has found over 30,000 restrictive property deeds to date. Researchers showed that current prices of Minnesota homes with racial covenants are 4 to 15 percent higher than identical homes without covenants. The Chicago Covenants project has already found over 100,000 properties with restrictive covenants, after searching about 20 percent of the city’s land records, and expects to find more as estimates of White-only property restrictions in that city range from 50 to 80 percent. In St. Louis, Missouri, the Dividing The City project found racial restrictions in about 80 percent of homes built in St. Louis County by 1950, for a total of about 100,000 parcels in the city and county combined.57

Figure 2.21: Restrictive covenants were more common in other US cities. Explore digital history projects with images from Seattle, Minneapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, and more by the National Covenants Research Coalition.

Challenging Racial and Religious Covenants

Across the nation, a coalition of Black homebuyers, real estate agents, civil rights activists, and NAACP attorneys mounted a political and legal battle to overturn racial as well as religious covenants during the 1940s. Their efforts focused primarily on two cities. In Detroit, with its recent history of White mob violence against Black wartime workers, the McGhee family purchased a home and were sued and harassed by a White neighborhood association for violating a racial covenant. In St. Louis, the Shelley family bought their home through a “straw-party,” a White buyer who purchased from a White seller and immediately resold to a Black buyer (often at a higher price). On the day the Shelleys moved in, the White neighborhood association delivered a legal summons to evict them for violating the covenant. As state courts defended these covenants, NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall and colleagues eventually persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to hear their appeal in January 1948 for the consolidated cases, known as Shelley v. Kraemer58

Meanwhile in Hartford, Black activists and journalists spoke out against racial covenants and called to ban them in Connecticut. The Hartford Negro Citizens’ Council, organized at the Women’s League in the city’s North End in 1941, publicly criticized a housing committee report by the Bridgeport Chamber of Commerce in 1945, which recommended racial covenants to create White-only suburban neighborhoods. Also, Black newspapers such as the Hartford Chronicle regularly reported on the national NAACP’s efforts to eliminate covenants in other states, and indirectly referred to their existence inside the state, with few details. Perhaps Hartford’s Black community did not know the full extent of racial covenants buried deep inside the property records in suburban town clerk’s offices.59

One Jewish civil rights ally supported Black Hartford activists by condemning covenants that restricted against race or religion. Simon Bernstein, an attorney and Democratic member of Hartford’s city council, sent a public letter to the chair of the Judiciary Committee at the State Capitol in April 1947, calling for a bill to prohibit restrictive covenants. One month earlier, Hartford’s Black press had run a story on New York State legislators raising their own anti-covenant bill. Bernstein called for Connecticut to ban property covenants regarding “nationality, color and religious belief” because these “un-American” practices are “contrary to public policy”. He argued that “real estate deals are public records” and “our Town Clerks are unwitting tools in transcribing prejudices on record” in a “government publication” that grants “immunity” to perpetrators. As an attorney who handled property transfers, Bernstein described but did not name “a nearby town” where a covenant for an entire subdivision restricted sales “to only non-semitic members of the Caucasian race,” a phrase he quoted directly. Hartford’s White press summarized Bernstein’s letter, but only the Black press published it in its entirety. Despite these efforts, Connecticut legislators waited for a decision from the federal government.60

Across the nation by the late 1940s, civil rights activists successfully began to turn the tide in the political and legal struggle against racial covenants. One month before the U.S. Supreme Court heard the NAACP’s consolidated Shelley v. Kraemer case, President Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights issued its report against racial covenants, and the US Department of Justice also filed a brief against this discriminatory practice. NAACP attorneys won the case when the US Supreme Court ruled restrictive covenants to be “unenforceable” in 1948. Yet the Court’s reasoning was not a striking blow against racism. First, the Court’s unanimous vote was 6-0, minus three justices who recused themselves without explanation, which suggested that perhaps they also owned racially restricted property. Second, the Court decided that private parties could voluntarily agree to restrictive covenants, but that the judicial system could not enforce these agreements because discriminatory state action violated the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In sum, the Shelley v. Kraemer ruling overturned the logic of the 1926 Buckley v. Corrigan decision, which refused to acknowledge legal enforcement of contracts as an act of government.61

While racist covenants were no longer enforceable, some Connecticut real estate developers continued to add them into deeds, which some town clerks continued to accept into the land records. In the Moodus Estates lakefront subdivision in East Haddam, Edward L. Parker, President of The Lake Realty Company, continued to sell land restricted only for “the Caucasian Race” at least into late 1949, more than a year after the US Supreme Court’s Shelley v. Kraemer ruling. Moreover, the East Haddam town clerk continued to accept and record a racist covenant at least until December 1950, more than two years after the Court’s decision.62

Similarly, when racial covenants were declared unenforceable, they did not disappear immediately across the nation. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) continued to require racial covenants for properties it insured until 1950, and continued to back mortgages for some White-only properties until 1962, according to The Color of Law author Richard Rothstein. Also, several state courts resisted the Shelley decision until a subsequent US Supreme Court decision in 1953, and the US Congress explicitly made restrictive covenants unlawful when it passed the US Fair Housing Act of 1968. Yet some local governments continued to accept restrictive covenants in property records until a US federal court struck down this practice in the 1972 Mayers v. Ridley ruling. Finally, even when local government clerks stopped accepting property deeds with unlawful covenants, generations of racist documents from the past continued to remain “on the books” in town halls across the US. When we total the number of race-restricted properties found so far by major public history projects (about 50,000 in Seattle-Washington State; 30,000 in Minnneapolis-St. Paul area; 100,000 in Chicago area; 100,000 in St. Louis area), a rough estimate of perhaps 1 million race-restricted homes across the US seems reasonable.63

Confronting the Legacy of Covenants

Although courts ruled that restrictive covenants were no longer enforceable, and town clerks eventually stopped filing racist property deeds into the public record, their legacy still influences us today. White Christian families that purchased restricted homes in the 1940s financially benefitted from government-supported segregation that boosted the value of property that guaranteed no Black or Jewish neighbors. Decades later, even when overtly racist housing preferences have declined, the descendants of 1940s homeowners benefitted from inherited wealth built upon a more intense era of prejudice. Even if someone’s White grandparents did not personally express racist views, if their home had a restrictive covenant, or was located in an all-White neighborhood created by covenants, those more-desirable qualities among today’s homebuyers probably put more dollars into their grandchildren’s pockets. In addition, the legacy of covenants also affected Black or Jewish homebuyers in more recent decades, who had to decide whether or not to live in a neighborhood with a documented past of being openly hostile to their presence.64

Inspired by the Segregated Seattle project and related work in other states, Connecticut residents have gradually begun to confront restrictive covenants in our past, strike them out of the public record, but not erase them from our historical memory. The process is not fast, but key steps have become more visible and gained momentum over the past decade.65

After we found restrictive covenants in West Hartford property records in 2010, we contacted current residents and invited them to publicly share their reflections in oral history video interviews, to build broader awareness of how racism shaped this predominantly White suburb. Two present-day White residents of West Hartford’s High Ledge Homes development were shocked to learn that their neighborhood had been protected by a 1940s White-only covenant, and sought to make sense of its meaning on their lives. Debra Walsh, an educator and actor, reflected on the White privilege that was attached to her decision to buy her home in 2010, shown in Figure 2.22. Although she had believed that the North had not exhibited such explicit racist policies, the direct evidence of race restrictive covenants convinced her that “West Hartford made a concerted effort to stay White and WASPy and that contributes to the feel of the neighborhood.” Walsh acknowledged how the explicit racism of the covenants in her own neighborhood made her feel uncomfortable with the White privilege she experiences. “It’s really hard to look really deep within and answer those questions,” she explained, “…when you live in the dominant class. Like you don’t know how to answer it.” Even though she knew the covenants are no longer enforceable, Walsh could see how “the legacy of the piece of land gets passed on to a feeling of a neighborhood,” a sense of White exclusivity that pervades even today, when barriers take on less overtly racial language.66

Figure 2.22: Watch the oral history video or read the transcript of the interview with Debra Walsh to hear how she learned about a race restrictive covenant in her West Hartford neighborhood. Interview copyrighted 2011 by Walsh and shared under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.

Yet while racial covenants make White West Hartford residents uncomfortable about the past, they remain an important piece of history, a hidden chapter that deserves more attention. Susan Hansen, a librarian and White resident who bought her home in the High Ledge Homes neighborhood in the 1990s, reflected on this theme in her 2011 oral history interview, shown in Figure 2.23. “I think this is something that people should know,” Hansen observed, “because there are people still living on my street who were here then, who must have been fully aware.” Hansen also emphasized the importance of knowing that racial covenants were not something that happened only in the Deep South long ago, but are a very recent part of Northern suburban history that should not be whitewashed out of memory. As Hansen concluded, “We need to know that we were being idiots up here, too, and it wasn’t somewhere else. It was here. It’s still here.”67

Figure 2.23: Watch the oral history video or read the transcript of the interview with Susan Hansen to hear her reflections about a race restrictive covenant in her West Hartford neighborhood. Interview copyrighted 2011 by Hansen and shared under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.

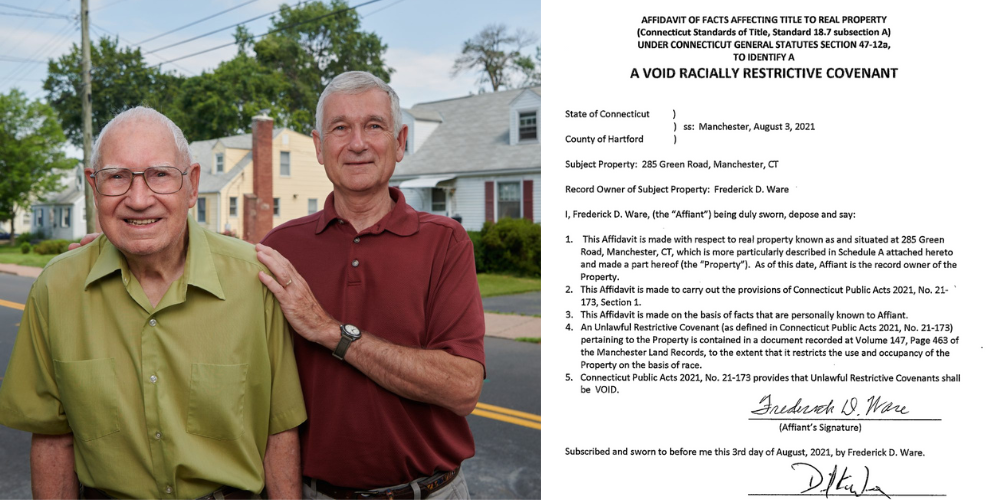

After David Ware wrote his 2020 academic study of restrictive covenants in Manchester, he took it one step further by raising it with reporters and lobbying Connecticut legislators to change the law. Ware initially began his study when his father revealed that their 1950s family home contained a racial covenant, hidden in the paperwork over five prior real estate transfers. Since a growing number of states had passed laws to address the legacy of covenants, Ware believed Connecticut needed one too. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement in early 2021, Ware drafted a plan to strike out racial covenants, which was initially sponsored by Manchester State Rep. Jason Doucette. At the Judiciary Committee, co-chair State Senator Gary Winfield revised it into a bill that quickly won unanimous support by the legislature and became law with the governor’s signature in 2021. Connecticut law now officially declares all unlawful covenants in land records to be void, and also creates a process for property owners with racist covenants in their title history to submit a simple form to identify and renounce it. Now, town clerks must mention the new process on their websites, make the forms available, and record completed forms at no cost to the property owner. The law is still relatively new, so not every town has fully complied, but as public awareness grows, local governmental awareness is expected to grow. The process to identify and renounce a racial covenant allows property owners to officially reject an expression of racism associated with their land, without removing it from the historical record. One of the first residents to identify and reject a void racial covenant was David’s 95-year-old father, Frederick Ware, as shown in Figure 2.24.68

Figure 2.24: Frederick Ware (left), with his son David, one of the first Connecticut residents to identify and renounce a void racial covenant in 2021. Photo copyrighted 2021 by UConn and reprinted under fair-use guidelines. Document from Town of Manchester property records, public domain.

In the New Haven suburb of Hamden, as current homeowners and community activists became aware of racial covenants in their property deeds, they spoke up and eventually connected with each other to publicly void them. Melinda Tuhus wrote a 1994 Hartford Courant opinion essay on discovering a racist covenant when purchasing her home in Hamden. At that time, Tuhus’s attorney discouraged her from attempting to strike out the restriction during the closing of her home purchase, arguing that making changes might “muddy the waters” and interfere with the sale. “You can’t change history,” her lawyer told her, yet Tuhus questioned the decision “to keep it hidden in musty tomes in the town clerk’s office.”69

Decades later during the Black Lives Matter movement in 2021, activists called attention to the history of racist property deeds in suburban developments that shaped Hamden’s Spring Glen neighborhood. When attorney June Gold attended Hamden’s Spring Glen Church in 2023, she learned about racial covenants from a speaker with Congregations Organized for a New Connecticut (CONECT). Gold also read about Ware’s work in Manchester and used her research skills to uncover several racial covenants in Hamden’s town records—to the surprise of the Town Clerk’s staff—and taught them about their legal obligation to publicize the 2021 state law. Currently, Gold works with community groups to build awareness and offers her free legal services to help current homeowners to identify and reject these racial restrictions. One of the many Hamden homeowners Gold assisted was Melinda Tulus, who wrote about wanting to “change history” and not “keep it hidden” in her 1994 article, and now had a way to make it happen.70

Under Connecticut Public Act 2021-173, each Town Clerk must post these forms, both on their website and inside the land records office, to allow property owners to identify and reject unlawful covenants, free of charge. Property owners may fill out and submit either form below:

- CT Identification and Renunciation of Unlawful Covenant

- OR

- CT Affidavit to Identify Racial Covenant, signed by notary

Help us continue the work to find and reject Connecticut’s racist covenants. In early 2024 we created the https://myCTdeed.com site to build public awareness and simplify the process for current owners to find and reject unlawful covenants from their property. To share with others, download our flyer shown in Figure 2.25. Learn more about How We Found Restrictive Covenants in this book and start research in your own community. If you know of similar property records with racial or religious restrictions anywhere in Connecticut, contact the authors.

Figure 2.25: Download our myCTdeed.com flyer to share with others.

About the authors and contributors: Tracey Wilson (Trinity 1976) wrote the first draft of the West Hartford portion for her 2010 article in the West Hartford Life magazine and published it in her 2018 Life in West Hartford book, which Vianna Iorio (Trinity 2019) revised for this book. David K. Ware and June Gold co-authored sections based on their covenant research in other Connecticut towns. Jack Dougherty collaborated with all and expanded the historical and comparative sections of this chapter. Ilya Ilyankou (Trinity 2018) and Jack Dougherty developed the interactive map, based on an earlier version created with UConn MAGIC. Katie Campbell Levasseur (Trinity 2011) researched restrictive property covenants, and both she and Candace Simpson (Trinity 2012) conducted oral history interviews.71

High Ledge Homes Inc., “Agreement Concerning Building Restrictions” (Volume 152, pages 224-5, maps #218, 222, 247, Property Records, Town Clerk, Town of West Hartford, Connecticut, June 10, 1940), https://github.com/ontheline/otl-covenants.↩︎

For an introduction to different types of restrictive covenants, see Examples in “National Covenants Research Coalition” (National Covenants Research Coalition, 2022), https://www.nationalcovenantsresearchcoalition.com.↩︎

See historical sources and tables in Ilya Ilyankou and Jack Dougherty, “Map: Race Restrictive Covenants in Connecticut, 1930s-50s” (On The Line, 2017), https://ontheline.github.io/otl-covenants/index-caption.html. Our current map is based on an earlier version, University of Connecticut Libraries Map and Geographic Information Center, “Race Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds, Hartford Area, 1940s,” 2012, http://magic.lib.uconn.edu/otl/doclink_covenant.html. See also David K. Ware, “The Black and White of Greenway: Racially Restrictive Covenants in Manchester, Connecticut” (Paper submitted for University of Connecticut School of Law, January 2020), http://ssrn.com/abstract=3546228, June Gold, David K. Ware, and Jack Dougherty, “Does My Connecticut Property Deed Contain A Racist Covenant?” 2024, http://myctdeed.com.↩︎

Corrigan v. Buckley, (271 US Supreme Court 323, May 24, 1926), https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11135903580197116691; Prologue DC, “Mapping Segregation in Washington DC,” 2015, http://prologuedc.com/blog/mapping-segregation. See how racial restrictions were promoted during the late 1920s by the National Association of Real Estate Boards, according to Paige Glotzer, How the Suburbs Were Segregated: Developers and the Business of Exclusionary Housing, 1890–1960 (Columbia University Press, 2020), jstor.org/stable/10.7312/glot17998; also also publicized by Richard Ely’s Chicago-based Institute for Research in Land Economics, based on Helen Corbin Monchow, The Use of Deed Restrictions in Subdivision Development, Studies in Land Economics (Chicago: The Institute for Research in Land Economics and Public Utilities, 1928), http://archive.org/details/useofdeedrestric00monc; LaDale C Winling and Todd M Michney, “The Roots of Redlining: Academic, Governmental, and Professional Networks in the Making of the New Deal Lending Regime,” Journal of American History 108, no. 1 (June 1, 2021): 42–69, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaab066.↩︎

James Jay Smith served as president of the Jas. Jay Smith Company, which later became The Shore & Lake Corporation, subsequently led by his son Avy B. Smith, but dissolved in 1964. “Saybrook Manor (Ad),” Hartford Courant, June 26, 1909, https://www.newspapers.com/image/369152232/; “Seaside Plots (Ad),” Literary Digest 34, no. 3 (July 17, 1909): 114, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Literary_Digest_a_Repository_of_Contempo/0wg8AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22highly+restricted+as+to+nationality%22&pg=PA114&printsec=frontcover; “Hudson River Bungalow Sites (Ad),” New York Times, April 18, 1909, https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/96896628/65F3364837FB4E59PQ/1?accountid=14405&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers; “Groton Long Point (Ad),” The Day (New London), August 14, 1913, https://www.newspapers.com/image/968855705/; “Niantic: Need Cooperation with Shore People,” The Day (New London), August 9, 1932, https://www.newspapers.com/image/968857164/; “The Shore & Lake Corporation and The Jas. Jay Smith Cmpany,” 2020, https://www.shoreandlakecorporation.com.↩︎

James Jay Smith and The Shore and Lake Corporation, “Lake Hayward Club Warrantee Deed” (Town of East Haddam, Connecticut, Land Records, vol. 56, p. 111, July 10, 1936), https://github.com/ontheline/otl-covenants/; “Thirty Lots Sold at Lake Hayward in Spring Period,” Hartford Courant, July 22, 1934, https://www.newspapers.com/image/369792065/; Charlyn Houston Montie, “History: Lake Hayward, East Haddam CT” (Property Owners’ Association at Lake Hayward, April 21, 2016), https://www.lakehaywardct.com/history/. TODO: confirm Ware’s notes that earliest racial covenant at Lake Hayward was dated 1930.↩︎

Alfred E. Hanbury, “Center Village Subdivision, Warranty Deed” (Land Records, Town of Newington, Connecticut, vol. 41, pp. 226-27,; maps 64, 66, 69, October 4, 1939), https://github.com/ontheline/otl-covenants; On Hanbury’s housing developments, see “Will Erect Houses in Newington: Alfred E. Hanbury,” Hartford Courant, March 29, 1937, https://www.newspapers.com/image/370101048/; “Hanbury to Build Brick Structure on Newington Site,” Hartford Courant, January 27, 1946, https://www.newspapers.com/image/367917727/; “Contractor Optimistic on Outlook,” Hartford Courant, May 14, 1950, https://www.newspapers.com/image/370251077/; “Alfred E. Hanbury: New Trustees and Officers Are Elected,” Hartford Courant, June 16, 1950, https://www.newspapers.com/image/370110307/; “Alfred Hanbury Dies,” Hartford Courant, February 5, 1970, https://www.newspapers.com/image/371464241/. Ware found no restrictive covenants in either Alandale or Belden Acres.↩︎

“100 New Homes To Be Built On High Ledge Tract: E. F. Hammel, New York Builder, Buys Tract From The R. G. Bent Co.” The Hartford Courant, March 31, 1940, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/docview/559299850?accountid=14405; “Ad: Modern Homes in High Ledge,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1940, https://www.newspapers.com/image/367307306/; High Ledge Homes Inc., “Agreement Concerning Building Restrictions”. See other West Hartford racial covenants in Ilyankou and Dougherty, “Map,” 2017.↩︎

Ware, “The Black and White of Greenway”, p. 4. See real estate transaction Frederick Ware, Vivian Ware, and Vincent Marcin, “Warrantee Deed Greenway Park Lot 35” (Town of Manchester CT Land Records, vol. 207, p. 62, February 24, 1950), https://recordhub.cottsystems.com/ManchesterCT/Search/Records/Details?IndexId=13094587, with 5 additional transfers between 1945-1949, back to the original race restriction in Lawrence A. Converse and Greenway, Inc., “Warrantee Deed, Greenway Park, Lots 15-17, 29-35,80-93” (Town of Manchester CT, Land Records, vol. 147, p. 463, October 7, 1942), https://recordhub.cottsystems.com/ManchesterCT/Search/Records/Details?IndexId=13333067. Interestingly, in personal correspondence Ware notes that while CT statute chapter 92 section 7.24(b) requires town clerks to record land records within thirty days, and nearly all property owners do so to make them public record, no CT law requires property owners to file land contracts with town clerks, meaning that some restrictive covenants might not have become public record. See Connecticut General Assembly, “Chapter 92 Section 7-24(b): Town Clerks. Recording,” in General Statutes of Connecticut, 2023, https://www.cga.ct.gov/current/pub/chap_092.htm#sec_7-24.↩︎

See Hamden table calculations and restrictive covenant land records in Ilyankou and Dougherty, “Map,” 2017.↩︎

See table calculations in Ilyankou and Dougherty. Manchester data from Ware, “The Black and White of Greenway”, p. 15↩︎

See more projects by members of the “National Covenants Research Coalition”. The earliest digital history project on racial property deeds probably was Wendy Plotkin, “Racial and Religious Restrictive Covenants in the US and Canada,” 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20151026174853/http://wbhsi.net/~wendyplotkin/DeedsWeb/, which states that content was posted online prior to 1999. On Seattle and Washington State, see James Gregory, “Segregated Seattle” (Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, 2006), https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/segregated.htm and Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington, “Racial Restrictive Covenants Project Washington State,” 2023, https://depts.washington.edu/covenants/laws.shtml. On Minnesota, see University of Minnesota Libraries, “Mapping Prejudice,” 2020, https://www.mappingprejudice.org and Aradhya Sood, William Speagle, and Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, “Long Shadow of Racial Discrimination: Evidence from Housing Covenants of Minneapolis,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY, September 30, 2019), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3468520. On the Chicago 80 percent estimate, see LaDale Winling, “Chicago Covenants” (Chicago Covenants, 2021), https://www.chicagocovenants.com and analysis by Robert Clifton Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948; repr., New York, Russell & Russell, 1967), http://archive.org/details/negroghetto00weav, p. 213 and chapter 13. On the St. Louis 80 percent estimate, see Colin Gordon, “Dividing the City: Race-Restrictive Covenants in St. Louis and St. Louis County,” 2022, https://dsps.lib.uiowa.edu/thedividedcity/ and Corinne Ruff, “80% of St. Louis County Homes Built by 1950 Have Racial Covenants, Researcher Finds” (STLPR: St. Louis Public Radio, January 31, 2022), https://www.stlpr.org/culture-history/2022-01-26/80-of-st-louis-county-homes-built-by-1950-have-racial-covenants-researcher-finds.↩︎

See also the role of Black homeowners and allies in Washington DC and other cities in Jeffrey D Gonda, Unjust Deeds: The Restrictive Covenant Cases and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/906234529, chapter 1. For contemporary accounts by Black activists and researchers, see Herman H. Long and Charles S. Johnson, People Vs. Property: Race Restrictive Covenants in Housing (Fisk University Press, 1947), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015020076074?urlappend=%3Bseq=1; Weaver, The Negro Ghetto, chapter 13. For national histories of restrictive covenants, see Clement E. Vose, Caucasians Only: The Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the Restrictive Covenant Cases (1959; repr., University of California Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520325647; Richard R. W. Brooks and Carol M. Rose, Saving the Neighborhood: Racially Restrictive Covenants, Law, and Social Norms (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013), http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/836206008; Rothstein, The Color of Law, chapter 5↩︎

“Negro Citizens’ Council Formation Is Discussed,” Hartford Courant, June 25, 1941, https://www.newspapers.com/image/369871907/; Hartford Negro Citizens’Council, “Letter to Editor: Segregation Opposed: Racial Problems in Housing Call for Post-War Settlement,” The Hartford Courant, April 5, 1945, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/hnphartfordcourant/docview/560252900/abstract/10CAE45732FD4C54PQ/8; “Middletown (Restrictive Covenants Reference),” Hartford Chronicle, January 11, 1947, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn92051342/1947-01-11/ed-1/?dl=page&q=restrictive+covenant&sp=1. Learn about Hartford’s 1940s Black press Hartford Chronicle, "1940?-1947", https://www.loc.gov/item/sn92051342.↩︎

“Bill to Outlaw Race Covenants (New York State),” Hartford Chronicle, March 8, 1947, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn92051342/1947-03-08/ed-1/; Simon Bernstein, “Letter to the Editor,” Hartford Chronicle, April 12, 1947, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn92051342/1947-04-12/ed-1/; “Bernstein Seeks End Of Restrictive Clauses,” Hartford Courant, March 28, 1947, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/docview/560759017?accountid=14405; “State Law Sought Against Racial Ban In Realty Deals,” Hartford Courant, April 2, 1947, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/docview/560760502?accountid=14405. Holly Hutton, A Brief Look Back: A Historical Overview of the Jewish Legal Community of Hartford, Connecticut (Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford, 2014), p. 40 briefly states that the anti-Jewish covenant was in West Hartford. But in our interview with Bernstein at age 98, he only recalled details about an anti-Black covenant in West Hartford that was settled out of court, not the anti-Jewish covenant in his 1947 letter, see Simon Bernstein, “Oral History Interview on Connecticut Civil Rights” (On The Line, Connecticut Digital Archives, August 1, 2011), http://hdl.handle.net/11134/120002:otl-bernstein. Tracey M. Wilson, “High Ledge Homes and Restrictive Covenants,” in Life in West Hartford (West Hartford Historical Society and Noah Webster House, 2018), https://lifeinwesthartford.org/world-war-ii-era.html#high-ledge-homes-and-restrictive-covenants described anecdotal accounts of anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic housing prohibitions in specific parts of West Hartford, but it is unclear whether or not these were written into property deeds or some other mechanism, as we have not yet found any religious covenants in Connecticut.↩︎

Shelley v. Kraemer, (334 US Supreme Court 1, May 3, 1948), https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12732018998507979172; Gonda, Unjust Deeds, p. 174↩︎

Edward L. Parker and The Lake Realty Company, “Warrantee Deed, Moodus Estates, Lot 8, Block 37” (Town of East Haddam, Connecticut, Land Records, vol. 66, p. 103, December 21, 1950), https://github.com/ontheline/otl-covenants.↩︎

Rothstein, The Color of Law pp. 85-91; Mayers v. Ridley, “Decision” (465 F.2d US Court of Appeals, DC Circuit, 630, March 1, 1972), https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=15478926121065691421.↩︎

Recall that in Minneapolis-St. Paul, current prices of homes with racial covenants are 4 to 15 percent higher than identical homes without covenants, according to Sood, Speagle, and Ehrman-Solberg, “Long Shadow of Racial Discrimination”.↩︎

On Seattle and Washington State, see Gregory, “Segregated Seattle” and Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington, “Racial Restrictive Covenants Project Washington State”. In Connecticut, the topic briefly arose in 1990 when the press reported that Richard Blumenthal, at that time the Democratic candidate for state attorney general, owned a home in Stamford CT with a race restrictive covenant. But this was driven by opponents in a political campaign, not a sustained effort for broader public awareness. See Michele Jacklin, “Civility Getting Trampled in Attorney General Race,” Hartford Courant, June 18, 1990, https://www.proquest.com/hnphartfordcourant/docview/1731514593/AF759DBAAC0E49D0PQ/1?accountid=14405&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers; Christopher Keating, “A Deja Vu Moment for Blumenthal,” The Hartford Courant, May 20, 2010, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/hartfordcourant/docview/257278442/abstract/C74B42362F2248FEPQ/2.↩︎

Debra Walsh, “Oral History Interview on West Hartford” (Cities, Suburbs, Schools Project, Trinity College Digital Repository, July 21, 2011), http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_ohistory/21. ↩︎

Susan Hansen, “Oral History Interview on West Hartford” (Cities, Suburbs, Schools Project, Trinity College Digital Repository, July 22, 2011), http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_ohistory/17.↩︎

Ken Dixon, “Whites-Only Rules Still Surface in Ct Property Records,” CT Insider, March 1, 2020, https://www.ctinsider.com/local/ctpost/article/Whites-only-rules-still-surface-in-CT-property-15096545.php; see public hearing testimony in Connecticut General Assembly, “Raised Bill 6665: An Act Concerning the Removal of Restrictive Covenants Based on Race and Elimination of the Race Designation on Marriage Licenses,” January 2021, https://www.cga.ct.gov/asp/cgabillstatus/cgabillstatus.asp?selBillType=Bill&bill_num=HB06665&which_year=2021; Connecticut General Assembly, “Public Act 21-173: An Act Concerning the Removal of Restrictions on Ownership or Occupancy of Real Property Based on Race and Elimination of the Race Designation on Marriage Licenses.” July 12, 2021, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2021/ACT/PA/PDF/2021PA-00173-R00HB-06665-PA.PDF; Jacalyn Severance, “Revelation of a Racist Property Restriction Leads to New State Law in Connecticut” (UConn Today, July 27, 2021), https://today.uconn.edu/2021/07/revelation-of-a-racist-property-restriction-leads-to-new-state-law-in-connecticut/; Susan Haigh, “State Lawmakers Work to Strip Old ’Whites Only’ Covenants” (Associated Press News, July 28, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/whites-only-property-covenants-race-ethnicity-56d67ad0dff72e8b71de768a24c90274; Frederick D. Ware, “Void Racially Restrictive Covenant” (Town of Manchester CT, Land Records, vol. 4659, p. 1076, August 3, 2021), https://recordhub.cottsystems.com/ManchesterCT/Search/Records/Details?IndexId=21189265.↩︎

Melinda Tuhus, “Vestiges of Racism Live on in Property Deeds (Op-Ed),” Hartford Courant, May 17, 1994, https://www.newspapers.com/image/175814134/.↩︎

Emily DiSalvo, “Hamden Confronts Legacy Of Segregation,” New Haven Independent, April 27, 2021, http://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/hamdensegregation_/; Emily DiSalvo, “Zoning Laws Have Led to a Segregated Hamden: Activists Are Working to Fix It” (HQNN.org, April 27, 2021), http://hqnn.org/2021/04/27/zoning-laws-have-led-to-a-segregated-hamden-activists-are-working-to-fix-it/; Dena Dupree, “Hamden in ’Black and White’: The Effects of Redlining Practices Today” (HQNN.org, December 7, 2021), https://hqnn.org/2021/12/07/hamden-in-black-and-white-the-effects-of-redlining-practices-today/; Austin Mirmina, “When Hamden Woman Found Racist Covenant in Her Property Deed, Rooting Them Out Became a Mission” (CT Insider, November 25, 2023), https://www.ctinsider.com/news/article/hamden-racist-property-deeds-spring-glen-18481356.php.↩︎

Tracey Wilson, “Taking Stock of High Ledge Homes and Restricted Covenants,” West Hartford Life 13, no. 2 (June 2010): 36–37, https://history.westhartfordlibrary.org/items/show/257; Wilson, “High Ledge Homes and Restrictive Covenants”; University of Connecticut Libraries Map and Geographic Information Center, “Race Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds, Hartford Area, 1940s”; Ilyankou and Dougherty, “Map,” 2017.↩︎

On The Line is copyrighted by Jack Dougherty and contributors and freely distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.