Writing Greater Hartford’s Civil Rights Past with ConnecticutHistory.org

by Elaina Rollins, Clarissa Ceglio, and Jack Dougherty

This chapter originally appeared in Connecticut History Review, whose editor granted permission to republish here with digital links and images.206 Several Trinity students’ ConnecticutHistory.org essays have been expanded into chapters in this book.

Through a campus-community partnership, Trinity College undergraduates have published essays under the guidance of http://ConnecticutHistory.org editors that enrich our understanding of twentieth-century civil rights history. Two years ago, Dougherty, a Trinity faculty member, and Ceglio, an editor for the Connecticut Humanities’ project, developed a public history writing assignment. Based on primary source research, students in the Cities, Suburbs, and Schools seminar have authored nearly a dozen short articles on too-often-forgotten histories of Northern injustice, focusing on housing discrimination, segregated education, and efforts to combat inequality in metropolitan Hartford. This assignment challenges undergraduates to accurately and clearly interpret past controversies for contemporary audiences, while instilling an appreciation for writing as an iterative process of reflection and refinement. Newer web-based tools enable drafts to be collaboratively reviewed by peers and the editor and also allow digital evidence–from archival documents, images, and interviews–to be incorporated directly into the essays. Overall, students’ reflections on this process emphasize the intrinsic value of actively contributing to the reshaping of Connecticut’s civil rights history on the public web, rather than simply earning a grade within the confined walls of the classroom.

ConnecticutHistory.org is an award-winning digital re-imagining of the traditional state encyclopedia that takes into account the ways in which information seekers use the internet not only for topic-specific searches but also for serendipitous discovery and, through Facebook, Twitter, and other social media, for sharing.207 Connecticut Humanities (CTH), the state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, developed this online resource in partnership with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University and the Digital Media Center of the University of Connecticut’s Digital Media & Design Department. Built using WordPress, a free, open-source content management system suited to the needs of web-based publishing, ConnecticutHistory.org debuted in 2012.208 Since then, by adding new material on a weekly basis, the site has grown to encompass more than 1,300 entries, 3,784 bibliographic records, more than 2,893 connections to digitized primary sources residing elsewhere on the web, and 258 resource pages–one for each of the state’s 169 towns and others on an expanding list of topics and people.209 Those who read and make regular use of the site include history buffs, educators and students (chiefly grades 7 through 12), and other repeat visitors with a sustained interest in state history. Of the roughly 16,700 visits to the site each month, many are the result of specific search queries as well as “click-throughs” from linked citations in other online publications, such as those of the National Geographic Society and Smithsonian Institution.210

Entries include lighter fare, such as the “Today in History” and “Who Knew?” series, which appeals to casual readers. But even short pieces encourage self-guided exploration, through tags as well as links to related ConnecticutHistory.org articles of greater depth. These more substantive entries are produced in collaboration with scholars and authors in the state’s museums, libraries, archives, historical societies, and universities.211 Such partnerships are essential to a sustainable, nonprofit publishing model built on collaborative content acquisition rather than commissioning. Editorial staff hold advanced degrees in public history, primary contributors are experts in their subject matter, and, unlike an academic journal, content does not undergo external peer review. The intent is to maintain a nimble publishing schedule, mindful of the public’s media consumption habits and responsive to topical interests created by contemporary concerns.

Importantly, the partnership model provides collaborators with an additional platform for disseminating scholarship produced in support of exhibitions, lectures, and other public fora that do not remain in the public eye. Scholars who publish in peer review journals and for academic presses also work with ConnecticutHistory.org to present this research in public-friendly form and thereby reach different audiences.212 Content, including essays written by Connecticut State Historian Walter W. Woodward, also comes from ConnecticutHistory.org partner Connecticut Explored magazine, which is co-published by Connecticut Humanities. Lastly, ConnecticutHistory.org structures its entries so that information seekers will be directed out to the institutions and repositories that hold and interpret primary source materials related to that particular slice of history. In other words, entries function as connectors by providing links to related institutions, primary source documents, online databases, digitized finding aids, places to visit, books to read, and other means of digging deeper into a given subject. This supports CTH’s mission to encourage the state’s communities to “explore new ideas and historical perspectives, and experience the cultural richness around them.”213

Helping to increase access to heritage resources is only one facet of the project’s commitment to public history. It also undertakes a range of collaborations designed to introduce students to the work of public history or dedicated to bringing lesser known histories of the state to wider general audiences.214 An example of the latter is a long-term effort to rethink how state encyclopedias can be more inclusive with regard to Native histories, particularly by including indigenous knowledge and voices. The Trinity College collaboration detailed here works toward both goals; its iterative writing assignment engages students in our shared criteria for sound historical methodology, clarity of expression, and use of multi-media documentation to educate non-specialist public audiences about historical patterns of racial discrimination in education and housing. This collaboration has inspired similar work with Wesleyan University, Central Connecticut State University, and Capital Community College.

For the past two years, Dougherty and Ceglio have collaborated on this ConnecticutHistory.org public history writing assignment during a three-week unit in his Cities, Suburbs, and Schools interdisciplinary seminar at Trinity.215 Students enrolled in the seminar investigate historical and contemporary relationships between schooling and housing in metropolitan Hartford, and this unit is only one example of student learning through community research with a partner organization. Dougherty and Ceglio co-designed the public history writing assignment which requires each student to compose a digital essay, not to exceed 1,000 words, on a designated topic of interest to readers of ConnecticutHistory.org.216 Since the undergraduates are not necessarily history majors, Dougherty generates an online “organizer” page: a list of prospective topics with links to relevant primary source materials, including oral history interviews prior students have recorded, print items he has scanned, and digital holdings from online repositories. Together, Dougherty and Ceglio tailor the list to highlight specific episodes in Greater Hartford’s past that lend themselves to a short essay, with an eye toward expanding civil rights history coverage on ConnecticutHistory.org.

Figure 8.14: Clarissa Ceglio teaches Trinity students Emily Meehan and Sean McGann how to write for ConnecticutHistory.org.

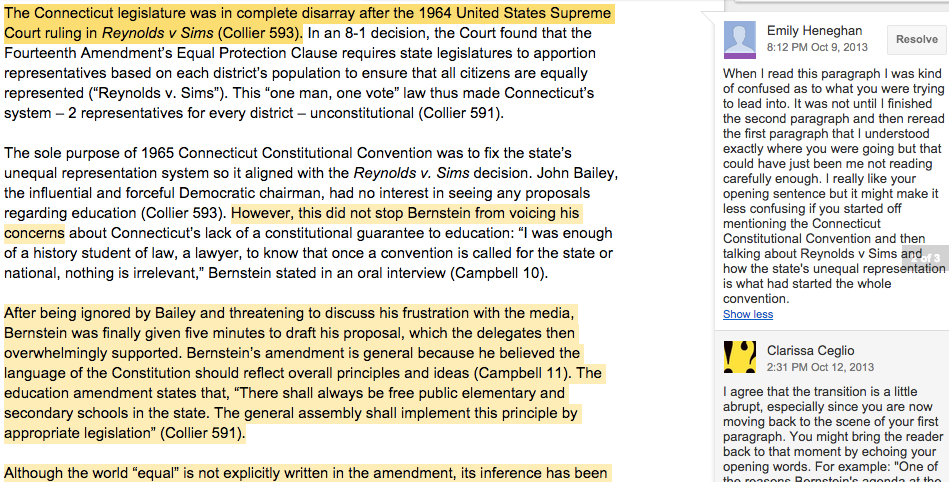

Unlike typical college papers, which are seen only by the student and the instructor, this public history writing assignment is designed for broader audiences, and its key stages occur on the public web. Ceglio visits the seminar to co-introduce the assignment and the editorial standards of ConnecticutHistory.org. Over the next two weeks, students select a topic from the list that interests them, then analyze and translate historical sources into engaging and accessible stories for diverse online audiences. They author their first drafts in a Google Document, a web-based tool that allows individuals to word-process their own text while simultaneously benefiting from online peer review by classmates, the instructor, and the editor, based on our common evaluation criteria.217

- Does the essay open with a compelling argument or story that explains the significance of the topic to Connecticut history? Does it inspire readers to think in new ways?

- Are the claims supported with appropriate evidence and reasoning? Is the historical research accurate and balanced, with full source citations?

- Does the writing style engage broad audiences, and provide sufficient background for those unfamiliar with the topic? Is the text well organized and grammatically correct?

- [For second draft only:] Are digital elements (such as links, images, and videos) thoughtfully integrated into the web essay, and properly credited?

After students revise their second drafts and embed links and images to relevant digital sources, all are required to post their work on the seminar’s public WordPress site. In accordance with the assignment guidelines, the editor and the instructor encourage selected students to revise and submit a third draft to ConnecticutHistory.org, with no guarantee that submissions will be accepted for publication. To date, about one-third of the students have eventually met the editorial standards for publication, which usually requires them to do additional work beyond the end of the semester. Multiple rounds of peer review and editing make the assignment much more real-world than the typical college essay, and students are challenged to raise their writing skills to contribute to an education larger than their own.

Figure 8.15: Students and mentors comment on draft essays using Google Documents.

Trinity student essays published on ConnecticutHistory.org cover a variety of topics, from discriminatory housing practices to efforts to combat educational inequality. These true tales of Northern injustice come as a shock to those who assume historical racial discrimination was limited to the South. By collaborating with ConnecticutHistory.org, Trinity students are able to spread awareness of this forgotten history. In his essay “The Effects of ‘Redlining’ on the Hartford Metropolitan Region,” student Shaun McGann discusses how current racial isolation in Hartford was shaped by past discriminatory housing practices. McGann writes that in 1937, the newly established Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps that color-coded neighborhoods based on investment opportunities in those areas; however, HOLC ratings were not always objective. Rather than simply relying on physical property conditions, HOLC frequently assigned poor investment values to neighborhoods with proportionally larger populations of blacks, immigrants, or members of the economic underclass–a process known as “redlining.” Another student essay by Mary Daly, “Race Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds,” elaborates on discriminatory practices designed to maintain the racial homogeneity of white suburbs in the 1940s. Some housing developers inserted restrictions into property deeds that prohibited “persons of any race except the white race” from owning or occupying selected homes in Greater Hartford, language that the United States Supreme Court deemed “unenforceable” in 1948 but was not made illegal until the 1960s. Furthermore, Emily Meehan’s essay, “The Debate Over Who Could Occupy World War II Public Housing in West Hartford,” recounts how white suburban residents and locally elected leaders effectively blocked African American workers from residing in federally subsidized wartime housing. Together, these pieces illuminate moments of Northern history that may have been forgotten over the years but have undoubtedly contributed to the racial housing patterns that still exist today in Greater Hartford.218

Other Trinity student essays highlight challenges against other forms of inequality by Connecticut activists, including the creation of the state’s education amendment and other more recent school desegregation programs. In “Five Minutes that Changed Connecticut: Simon Bernstein and the 1965 Education Amendment,” Elaina Rollins tells the story of Simon Bernstein, a Hartford lawyer and author of Connecticut’s education amendment, which guarantees free elementary and secondary schooling for children across the state. Bernstein not only lobbied against racially restrictive covenants, such as those described in Daly’s essay, he also advanced the amendment on his own accord, despite significant obstacles from his political superiors. Connecticut’s education amendment later served as the basis for school inequality lawsuits such as the 1989 Sheff v. O’Neill case, which charged that Greater Hartford’s racially isolated schools were unconstitutional. Trinity student Brigit Rioual discusses the aftermath of this landmark case in her essay “Sheff v. O’Neill Settlements Target Educational Segregation in Hartford.” The Connecticut Supreme Court ruled in 1996 that the state must provide equal educational opportunities for Hartford students, but Rioual’s piece explains how Connecticut initially failed to follow through on the court’s order. While the state had agreed to enroll at least 30 percent of Hartford minority children in “reduced isolation” settings (i.e., schools where minorities made up less than three-quarters of the student body), only 17 percent had been achieved by 2007. Rioual’s essay tells a relatively recent story, but the roots of the Sheff case date back to historical patterns of racial segregation and educational advocacy efforts. By collaborating with ConnecticutHistory.org, Trinity students are helping to make public important connections between past injustices and present reforms. Their contributions illustrate in an engaging, informative manner how historical knowledge can help us understand present-day circumstances.219

Students who complete additional rounds of editing with ConnecticutHistory.org experience memorable transitions when they become published authors. College students frequently spend hours on assignments that are ultimately read only by their professor, so to see one’s name in the byline on a respected public website validates seminar participants’ research and writing in a way that a grade alone cannot. Several students have commented that before working with ConnecticutHistory.org, they doubted their own skills as writers. Victoria Smith-Ellison, a sophomore at the time, said that although she struggled with composing essays before beginning college, this collaborative public history project “allowed me to be comfortable with my writing skills that I have learned thus far.” Other students noted how the collaborative nature of the project inspired them to improve their essays even after handing in the required drafts. “After I got the comments [from Dougherty, Ceglio, and classmates], I was at first very overwhelmed,” said Mary Daly. “But I actually really enjoyed polishing my work. I think that [the editing process] helped me, because in the future, I can actually tackle a process and finish it through all the way to the end.”

Collaborating with ConnecticutHistory.org also encouraged undergraduate students to recognize themselves as authors contributing to a broader public history, as shown in the video clip in 8.16. Nicole Sagullo, a science student who did not have much experience with humanities writing before Dougherty’s course, said that after her article was published, she discovered that another student on campus had cited her essay in an assignment. “It was just a really good feeling to think that someone had looked at it and read it who wasn’t in that particular class with us,” Sagullo explained. Another seminar participant described how collaborating with a community partner elevated her own view and expectations of herself. “You felt more like a contributor or colleague rather than just a student handing in an assignment,” explained Amanda Gurren. “We felt like we were working with people rather than for them… We felt very respected.” Through several rounds of feedback and revisions, collaborative writing not only incentivizes students to seek improvement in their own work, but also view themselves and their peers as published contributors to Connecticut’s online history.220

Figure 8.16: Watch the video clip on Trinity students reflecting on their writing process with ConnecticutHistory.org in 2013.

What are the essential ingredients behind successful public history writing collaborations such as this? First, all participants–students, faculty, and editors–must be motivated to devote additional time and energy to work together on a common goal, with support from their respective institutions. In our partnership, everyone wins. Undergraduate learning benefits from the talent and attention provided by an additional guest writing instructor and evaluator, and in return, high-quality essays on forgotten aspects of civil rights history enrich Connecticut’s understanding of its past. Second, our collaboration became easier with advances in web-based writing tools and online publications. Nowadays, students can write and quickly receive multiple peer reviews from readers, both on and off-campus. Since ConnecticutHistory.org favors shorter essays written for broad audiences, this public history assignment works for a wide array of undergraduates, and its entirely online publication means a speedier turnaround for student contributors who meet their standards. Third, because all of the essays can easily be found on the public web–rather than locked behind a paywall or available only in selected libraries–our contributions to state’s civil rights history are widely accessible and more valuable to readers both inside and outside of Connecticut. We take pride that Tom Sugrue, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the nation’s leading scholar of Northern civil rights history, took a brief moment to publicly recognize the students’ essays during his April 2014 keynote address to the Association for the Study of Connecticut History.221

For many historians, the digital era raises fears about the future of our profession. What does it mean when anyone can instantly publish their historical interpretation, whether good or bad, on the Internet? How do newer technologies change–and perhaps challenge–what it means to do history? Rather than avoiding the digital turn, we believe that it also provides an ideal opportunity–if wisely exercised–to bring a younger generation to the table and to fully engage them in doing what historians have always done: telling true and meaningful stories about the past for audiences broader than ourselves.222

Trinity College Student Contributions to ConnecticutHistory.org

Race Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds, by Mary Daly ’15. “No persons of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot… .” Language such as this still appears in Hartford-area housing covenants today.224

Connecticut Takes the Wheel on Education Reform: Project Concern, by Amanda Gurren ’15. As one of the earliest voluntary busing programs in the US, Project Concern sought to address educational inequalities.225

The Effects of “Redlining” on the Hartford Metropolitan Region, by Shaun McGann ’14. Historical data reveals long-term patterns of inequality that can be traced back to now-illegal practices adopted by federal and private lenders in the 1930s.226

The Debate Over Who Could Occupy World War II Public Housing in West Hartford, by Emily Meehan ’16. In the 1940s, African American war workers eligible for government-funded housing found access restricted to some properties despite vacancies.227

Sheff v. O’Neill Settlements Target Educational Segregation In Hartford, by Brigit Rioual ’14. This landmark case not only drew attention to inequalities in area school systems, it focused efforts on reform.228

Five Minutes that Changed Connecticut: Simon Bernstein and the 1965 Connecticut Education Amendment, by Elaina Rollins ’16. “There shall always be free public elementary and secondary schools in the state. The general assembly shall implement this principle by appropriate legislation.”229

How Real Estate Practices Influenced the Hartford Region’s Demographic Makeup, by Nicole Sagullo ’14. Persistent segregation is the historic legacy of steering and blockbusting, two discriminatory tactics that played a role in shaping suburban neighborhoods.230

Hartford’s Great Migration through Charles S. Johnson’s Eyes, by Victoria Smith Ellison ’15. During the Great Migration of the early 1900s, African Americans from the rural South relocated to Hartford and other Northern cities in search of better prospects.231

Education/Instrucción Combats Housing Discrimination, by Savahna Reuben ’15. This group’s bilingual name reflected its educational mission as well as its dedication to unified, multicultural cooperation for the common good.232

About the authors: Elaina Rollins (Trinity 2016), Clarissa Ceglio, and Jack Dougherty co-wrote this essay based on their collaboration in the Cities Suburbs and Schools seminar.

Elaina Rollins, Clarissa Ceglio, and Jack Dougherty, “Writing Greater Hartford’s Civil Rights Past with ConnecticutHistory.org,” Connecticut History Review 53, no. 2 (2014): 220–26, https://ontheline.trincoll.edu/writing.html.↩︎

The website’s permanent web address is http://connecticuthistory.org/. ConnecticutHistory.org received the 2013 New England Museum Association First-place Publication Award for excellence in design, production, and effective communication in websites for organizations with institutional budgets over $500,000.↩︎

Clarissa Ceglio, “ConnecticutHistory.org Opens a New Gateway to Our State’s Past” (ConnecticutHistory.org, May 22, 2012), https://connecticuthistory.org/connecticuthistory-org-opens-a-new-gateway-to-our-states-past/.↩︎

ConnecticutHistory.org site statistics as of June 2014; data on file Connecticut Humanities.↩︎

Total site visits in fiscal year 2013-14 were 200,748, a 226% increase over fiscal year 2012-13 visitation (88,483); data on file Connecticut Humanities.↩︎

Clarissa Ceglio, “The Dos, Don’ts and Dividends of Digital Collaboration.” NEMA News, Winter 2013, https://www.academia.edu/3223779/The_Dos_Don_ts_and_Dividends_of_Digital_Collaboration.↩︎

Ben Railton, “Yung Wing, the Chinese Educational Mission, and Transnational Connecticut” (ConnecticutHistory.org), accessed June 19, 2019, https://connecticuthistory.org/yung-wing-the-chinese-educational-mission-and-transnational-connecticut/.↩︎

Connecticut Humanities, “Mission,” accessed July 11, 2014, http://cthumanities.org/about/mission.↩︎

An additional example of how ConnecticutHistory.org supports student scholarship is its ongoing partnership with the state’s National History Day program. See Rebecca Taber-Conover, “History Day in Connecticut,” Connecticut History 51, no. 2 (Autumn 2012): 261–64.↩︎

Educational Studies 308: Cities, Suburbs, and Schools syllabi, Fall 2012 and Fall 2013, Trinity College, http://commons.trincoll.edu/cssp/seminar/prior-syllabi/↩︎

Dougherty and Ceglio, “Compose Web Essay for ConnecticutHistory.org,” Cities Suburbs and Schools seminar, Trinity College, October 13, 2013, http://commons.trincoll.edu/cssp/seminar/assignments/connecticut-history-entry/↩︎

Jack Dougherty, “Co-Writing, Peer Editing, and Publishing in the Cloud,” in Web Writing: Why and How for Liberal Arts Teaching and Learning, ed. Jack Dougherty and Tennyson O’Donnell (University of Michigan Press, 2015), http://epress.trincoll.edu/webwriting/chapter/dougherty-cowriting.↩︎

McGann, “The Effects of ‘Redlining’ on the Hartford Metropolitan Region”; Mary Daly, “Race Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds” (ConnecticutHistory.org, January 2013), http://connecticuthistory.org/race-restrictive-covenants-in-property-deeds/; Meehan, “The Debate Over Who Could Occupy World War II Public Housing in West Hartford”.↩︎

Elaina Rollins, “Five Minutes That Changed Connecticut: Simon Bernstein and the 1965 Connecticut Education Amendment” (ConnecticutHistory.org, January 2014), http://connecticuthistory.org/five-minutes-that-changed-connecticut-simon-bernstein-and-the-1965-connecticut-education-amendment/; Brigit Rioual, “Sheff v. O’Neill Settlements Target Educational Segregation In Hartford” (ConnecticutHistory.org, April 2013), http://connecticuthistory.org/sheff-v-oneill-settlements-target-educational-segregation-in-hartford.↩︎

Student quotations excerpted from CTHprograms, “Make Life Collaborative” (YouTube video, April 8, 2013), http://youtu.be/NuWg9Jrkrpw.↩︎

Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2009), http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0812970381; See also Twitter post at ASCH meeting, April 5, 2014, https://twitter.com/DoughertyJack/status/452440673942536192↩︎

Jack Dougherty and Kristen Nawrotzki, eds., Writing History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.3998/dh.12230987.0001.001.↩︎

Connecticut History, “Trinity College Students Call Attention to Histories of Inequality”.↩︎

Amanda Gurren, “Connecticut Takes the Wheel on Education Reform: Project Concern” (ConnecticutHistory.org, April 2013), http://connecticuthistory.org/connecticut-takes-the-wheel-on-education-reform-project-concern/.↩︎

McGann, “The Effects of ‘Redlining’ on the Hartford Metropolitan Region”.↩︎

Meehan, “The Debate Over Who Could Occupy World War II Public Housing in West Hartford”.↩︎

Rioual, “Sheff v. O’Neill Settlements Target Educational Segregation In Hartford”.↩︎

Nicole Sagullo, “How Real Estate Practices Influenced the Hartford Region’s Demographic Makeup” (ConnecticutHistory.org, February 2013), http://connecticuthistory.org/how-real-estate-practices-influenced-the-hartford-regions-demographic-makeup/.↩︎

Victoria Smith-Ellison, “Hartford’s Great Migration Through Charles S. Johnson’s Eyes” (ConnecticutHistory.org, February 2013), http://connecticuthistory.org/hartfords-great-migration-through-charles-s-johnsons-eyes/.↩︎

Savahna Reuben, “Education/Instrucción Combats Housing Discrimination” (ConnecticutHistory.org, December 2014), http://connecticuthistory.org/educationinstruccion-combats-housing-discrimination/.↩︎

On The Line is copyrighted by Jack Dougherty and contributors and freely distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.